Passion For Paderewski

by General Edward Rowny

I would like to recount briefly how my passion for Paderewski affected not only my career but my entire life. At times I will be repeating parts of my biography but I will only do so where it is necessary to put Paderewski’s influence on me in proper context.

ELR Discovers IJP

My passion for Paderewski began at an early age, when I was six. I was living with my grandmother, who loved listening to Paderewski’s piano virtuosity on her Red Seal 78 rpm phonograph records. She greatly admired Paderewski as a statesman and scholar and especially revered him for his integrity.

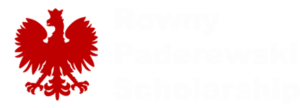

ELR’s Pantheon: Polish Hero #1: Pulaski

She steeped me with information about Poles who fought for American independence. The first was Count Casimir Pulaski, who initially failed to convince George Washington that there should be a cavalry corps in the United States Army. The General believed that horses should be used only to carry supplies or messengers. Unable to convince Washington of the value of cavalry in combat, Pulaski purchased 200 mounts at his own expense in Poland and had them shipped to the United States. With volunteers who were good horseman, he formed the first cavalry regiment of the United States Army. By maneuvering against the flanks and rear of the enemy the cavalry soon demonstrated that it was of great value. Pulaski lost his life leading a cavalry charge at Savannah where he is buried.

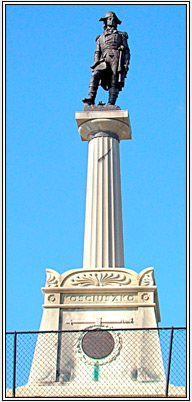

My uncle, August Radziszewski designed and raised money to build a statue to Pulaski, which is situated in my home town of Baltimore, Maryland. Pulaski’s cavalry was the forerunner of Civil War cavalry leaders such as George Custer and Stonewall Jackson. Nearly a century later, when horses were replaced by armored vehicles, the new cavalrymen were Rommel, Montgomery and Patton. Peeking into the future, armored vehicles were replaced by armed helicopters in Vietnam and the latest successors to Pulaski were Generals Kinnard and Moore.

ELR’s Pantheon: Polish Hero #2: Kosciuszko

The second Polish hero was Thaddeus Kosciuszko, who was General Washington’s chief engineer and who designed the defenses at Saratoga. General Washington credited Kosciuszko with turning the tide of the American Revolutionary War. Kosciuszko built the defenses at the Hudson River Narrows and put across an iron chain to prevent British troop ships from delivering reinforcements to the British army in Canada. This site became the home of my future alma mater, West Point, built in 1802. Cadets of the first classes donated generous portions of their allowances to build a platform in 1825 on which the magnificent statue of Kosciuszko rises above the parade ground.

During the War, Kosciuszko refused his pay as a U.S. Army officer, saying it was his contribution to American independence. One of the first acts of the U.S. Congress of the newly independent United States awarded Kosciuszko his back pay. Still feeling that he should not be paid for contributing to such a noble cause, he instructed Thomas Jefferson, his good friend and executor of his will, to use the money to purchase plantation slaves and set them free.

ELR’s Pantheon: Polish Hero #3: IJP

My grandmother’s third hero was not a General but a Polish citizen, Ignacy Jan Paderewski. He was not only a brilliant pianist and composer, but a distinguished scholar and eminent statesman. Paderewski formed the Kosciuszko Squadron, a force of American and Canadian volunteers who joined the French Army.

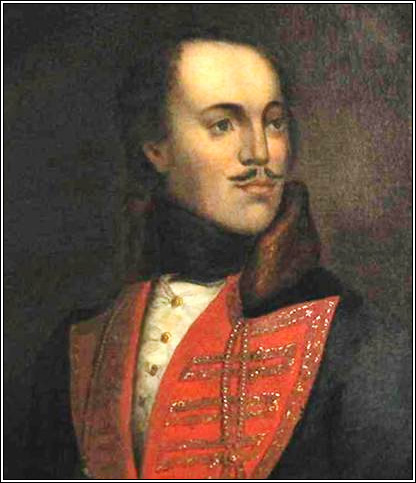

At the outbreak of the war, Paderewski doggedly pursued Colonel House, President Woodrow Wilson’s primary adviser, to arrange a meeting. Charmed by the handsome and eloquent pianist, House accepted Paderewski’s argument that the Polish Nation should be resurrected. House introduced Paderewski to the President, who likewise fell under his charm. He was the inspiration for the famous 13th point of the Versailles Treaty.

At Versailles, Paderewski had to bring all of his persuasive powers to bear once again. Lloyd George and Georges Clemenceau felt that resurrecting Poland would only upset stability on the continent. The unrelenting Polish statesman succeeded in turning them around to his point of view. Clemenceau was so impressed by Paderewski that he called him “one of God’s most noble creatures.”

In 1919 Paderewski became the first Prime Minister and Minister of Foreign Affairs of the new Polish state. In 1922 Paderewski returned to the concert stage where he once again regained his title of the world’s best pianist.

On September 1, 1939, when the Nazis invaded Poland, Paderewski was determined to convince President Roosevelt that the U.S. should prepare for war. Although sympathetic, the President had to act stealthily to rebuild and rearm the United States forces because the public and Congress had turned to isolationism. Although ill, Paderewski criss-crossed the United States pleading that the country prepare for war. In failing health, he died in New York City on June 29, 1941.

The Nazi Threat Becomes Clear

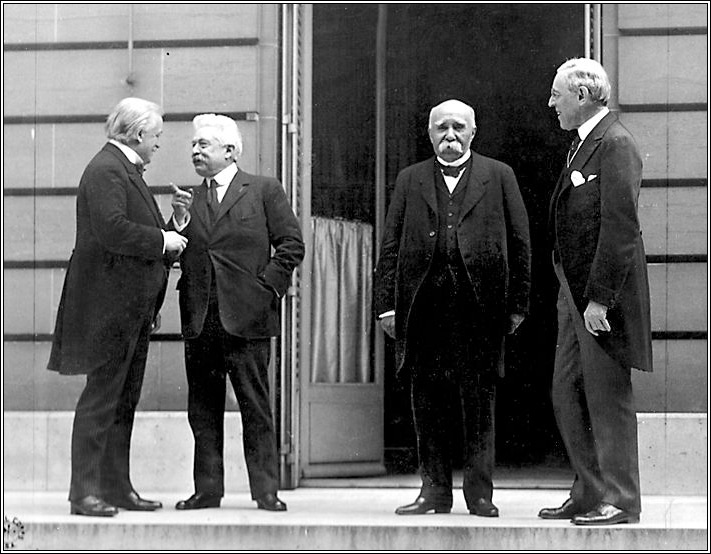

The second phase of my passion for Paderewski began when I attended the XI Olympics in Berlin in 1936. Earlier that summer I began a semester’s study at the Jagiellonian University in Cracow, Poland. I had been awarded one of the first scholarships to Poland by the recently established Kosciuszko Foundation. Studies at the Jagiellonian University were arranged in a manner that allowed me to travel around Europe, including the trip to Berlin to watch the Olympics.

Although very high up in one of the cheaper seats, I was thrilled to see the African-American, Jesse Owens, win his four gold medals. My thrill turned to disgust when I saw Hitler turn his back on Owens during the presentations of the medals. As night fell and the evening torch-lit parade began, my feelings of disgust turned to those of fear. The fervor and stridency with which the goose-stepping Nazis thrust out their hands and yelled “Heil Hitler” convinced me that a war in Europe was not only inevitable but imminent. Returning home, I described the terrifying scene at the Berlin stadium to my grandmother and told her of my conviction that war in Europe was near.

“You’re right,” said my grandmother, “and shortly afterwards the United States will become involved. You’re studying engineering at Hopkins, and like Kosciuszko, you should prepare to put your engineering skills to work in war.”

ELR: Johns Hopkins and ROTC

On returning to Johns Hopkins I decided to take my ROTC classes more seriously. When I entered my senior year I was elected to the honorary military society “Scabbard and Blade,” awarded to those who stood in the top five percent of the ROTC Squadron. Since there were only 50 men in a squadron I was one of two cadets so honored. Upon graduation, all members of the squadron would become 2nd Lieutenants in the Army reserve but only one would be inducted into the regular army.

Only 19 at the time, I was a skinny teenager while my colleague was a mature and robust young man of 22. He was a truly outstanding cadet with great command presence. It was obvious that he would be chosen to receive the one regular Army commission and I would be commissioned an officer in the Army Reserves. My grandmother, once again, had the solution.

“Apply to West Point,” she said, “where after 4 years you will be guaranteed a commission in the regular Army. You won’t have to study very hard because the curriculum at West Point is almost identical to the one you are finishing at Hopkins. You will have time to read the history of the Peloponnesian Wars, War and Peace, and other military classics for which you had no time at Hopkins. Not having to earn your board, you will have 3 square meals and be taking physical training and in 4 years you will look like an officer. You will receive more military instruction than you were able to get as an ROTC cadet.”

I followed her advice and was able to get an appointment to West Point, took the physical and academic exams, and was admitted to the U.S. Military Academy. On June 11, 1937 I received my Bachelor of Science degree and my gold bars as a 2nd Lieutenant in the U.S. Army Reserve Corps. Three weeks later, on July 1, 1937 I took off my gold bars and became a plebe as West Point with the rank of Private.

My first day at West Point was quite a shock. I had heard about the harassment plebes undergo but did not anticipate that it would be so stressful and physically demanding. This time, being older than my classmates, I hoped I would be treated with some respect. There was none. Like the others, I outranked only the Superintendent’s cat. Still, I had lived through the Depression and was used to hard-knocks. I soon adjusted to the pace and took my stern, and at times harsh, treatment by upperclassmen in stride.

I cannot resist telling about how I learned that the pronunciation of Kosciuszko was “Koz-kee-yozko.” An upperclassmen pointing to the large monument on the West Point plain asked me “Dumb John, what’s the name of that monument?”

I answered, “Kos-chu-sko Monument.”

“Take 10 push-ups, he said, “It’s the Koz-kee-yozko Monument.”

A week later he returned with the same question and I gave him my same answer.

“Take 20 push-ups,” he said. “I told you last week how to pronounce the name of that monument.”

“Sir”, I said politely, “I am of Polish origin and know how to correctly pronounce the name of the Kosciuszko Monument.”

“Dumb John,” he said “Plebes don’t know anything! You’d better learn how to pronounce it.”

The same pattern continued regularly for the next 49 weeks. Each time I was asked a question I gave the same answer and each time I was awarded 20 push-ups.

A year later, I became a 2nd class yearling and no longer a plebe. The upperclassman, who had weekly quizzed me on the monument, shook my hand and said, “Well, Mr. Yearling, what’s the name of that monument”?

After I gave him my usual answer, he smiled broadly and said, “Of course it’s pronounced Kosciuszko. I too am of Polish origin.” His name was Andrew Goodpaster and we were friends until his recent death.

I sailed through my second year at West Point enjoying reading military history as well as Ernest Hemingway, Jack London and Joseph Conrad. I also had the opportunity to read books about my three Polish heroes; Pulaski, Kosciuszko, and Paderewski.

On September 1, 1939, at the beginning of my third year, Nazi Germany attacked Poland. The predictions my grandmother and I made in 1936 were coming true. To keep up with events in Poland, I formed a group of 10 cadets of Polish origin which I called the Kosciuszko Squadron. We met monthly to follow the war in Europe and to read newspaper clippings of Paderewski’s speeches. We marveled that the aging pianist had the energy to make a speech a day as he went from city to city urging his listeners to prepare for the war he said would soon involve the United States.

The Kosciuszko Squadron also made monthly visits to tidy up The Kosciuszko Garden on the escarpment behind Cullum Hall at the Academy. This small garden at the end of Flirtation Walk on the banks of the Hudson River was the place where Kosciuszko went to rest and meditate.

ELR at IJP’s Funeral

On June 11, 1941 I graduated from West Point with a second Bachelor of Science degree and was commissioned a 2nd Lieutenant in the Army, this time as a regular officer. On June 29, about two weeks after graduating, I heard over the radio that Ignacy Jan Paderewski had died. I went to New York to attend Paderewski’s funeral. On the beautiful sunny day of the services 5,000 people, I among them, jammed into Fifth Avenue to hear Cardinal Spellman’s eulogy over loudspeakers. The Cardinal said that Paderewski’s remains could not be returned to his native Poland because it was now occupied by the Germans. The president, he said, wanted to bury Paderewski in Arlington Cemetery, our nation’s shrine, but was unable to do so because the cemetery was reserved for U.S. citizens. Instead, President Roosevelt decreed that Paderewski’s remains be interred temporarily at Arlington Cemetery until Poland was again free. Several days later, at home in Baltimore, my grandmother had me promise that I would do everything I could during my lifetime to return Paderewski’s remains to Poland.

Returning IJP to Poland

Thus began a 50 year struggle which finally succeeded when I returned Paderewski’s remains, less his heart, to Warsaw in 1992. Like Chopin, Paderewski willed that his heart and remains be buried separately. Chopin wanted his body to remain in France, with that of Georges Sand, and that his heart be returned to Poland. Paderewski willed differently. He wanted his heart to remain in United States but said nothing about where his remains should be buried.

Paderewski’s heart mysteriously disappeared and was found in 1980, nearly 4 decades later. The return of his body to Poland was a highly complicated and difficult task. Among the many obstacles I had to overcome was a lawsuit where I was accused of being a grave robber. Space does not permit me to recount this interesting and bizarre story.

IJP Inspires ELR

From Paderewski’s death in 1941 until the present, his example of integrity, courage, and patriotism served as an inspiration. As I learned more about Paderewski’s philosophy, I was impressed that he stressed how freedom and democracy can best be promoted through education and the arts. I was not talented artistically, but did my best by learning to play the classics on the harmonica. Following Paderewski’s dictum concerning education during my career, I earned two master’s degrees and a PhD, the latter taking 19 years of night and weekend classes.

Throughout my career, whenever I faced a difficult decision, I relied on two sources of strength. One was the West Point motto, “Duty, Honor, Country” and the other was the wisdom and example of Paderewski. I relied on these two resources to see me through a half dozen crises during my career. I will cite only three.

IJP Guides ELR #1: Pentagon

The first was in 1952 when I was reprimanded by the Secretary of the Army. He admonished me for teaching unapproved doctrine at the infantry school. While his allegation was true, I made it clear that my after-hours unofficial voluntary PROFIT-Times sessions were mind-stretching exercises. These were intended to get students to think ahead on how we might use ground-launched atomic weapons and armed helicopters in future battles.

Nevertheless, the Secretary felt that I was violating instructions. I was crushed at having been reprimanded and thought my career was finished. However, relying upon the West Point motto and Kosciuszko’s example which merged perfectly, I decided to lick my wounds and carry on. My grandmother, although aging but mentally sharp, agreed. Within 3 years the incident blew over and the reprimand, which was oral and not a matter of record, was forgotten. I was glad I did not resign.

IJP Guides ELR #2: SALT

A second serious crisis occurred in 1978-1979. As Chief Strategic Arms Negotiator, I became convinced that the SALT II Treaty we were about to sign with the Soviets was unequal and unverifiable. Although the Joint Chiefs of Staff said the treaty would be a “modest but useful step,” I felt that we could not take two successive steps across a chasm. Instead, we would fall to the bottom of the chasm, endangering U.S. national security.

As I agonized over what to do, I once again fell back on my twin resources, the West Point motto and Paderewski’s example. The answer which emerged was that I should go with my dilemma to Secretary of State Vance. In December 1978, he asked me not to criticize President Carter publicly so long as the treaty was being negotiated. He asked me to continue negotiations to see if we could arrive at an equitable treaty by the projected signing date, June 15, 1979. He added that if, when President Carter signed the treaty, I was still unhappy with it, I should then resign from the U.S. Army.

Following the West Point motto, I was convinced that the honorable course of action was to be loyal to the president and not leak my feelings to the press. I believe that Paderewski would have adopted the same course of action. After I resigned I felt free to criticize the treaty and lead a group which convinced the Senate not to ratify it. When the Soviets invaded Afghanistan in December 1979, President Carter withdrew the SALT II Treaty from consideration by the Senate.

IJP Guides ELR #3: PSF

The final phase of my passion for Paderewski is that I am spending the remainder of my life promoting his legacy. In addition to writing articles and giving speeches, I decided in 2004 to establish the Rowny-Paderewski Scholarship. This scholarship is designed to bring an outstanding Polish University student to Georgetown University each year to study American style democracy and the free capitalist system. I paid for the first year’s scholarship and turned the task of administrating the scholarship over to The Fund for American Studies (TFAS). While TFAS would select the winner and handle the details of the schooling with Georgetown University, I would use their assistance to raise additional funds.